Shoulder surgery is kind of like getting drilled in the face with a wine opener. The only major differences are 1) the location of the drilling, and, 2) in the event of drilling your face, you’d probably die, but in the case of your shoulder, you will want to die.

OK, it’s not that bad, but it can be if you don’t have strong enough pain medication (more on that later).

I’ll break this down into a few sections for readability, which should allow you read whatever you care about (assuming you care about something).

Background of the Injury

I’m skiing with my dad and a few of our French friends in Zermatt; you can’t see much, especially not the Matterhorn. We are in shin/knee-deep powder and I come to a stop, but become slightly unbalanced and am barely standing, with the majority of my weight resting on my pole. My friend sees this and pushes me over. Annoyed, I stand back up and realize that I’m not going to push him over because he is ready for it, standing on two skis — he is also 200-220 lbs and about 6’4. So I decide to pick him up, because that’s obviously the better idea.

I wrap my arms around his legs at a very awkward angle and pull with all of my might. (Imagine standing on skis or rollerblades, rotating your torso 90 degrees to the right, and then lifting lots of weight.) What might happen is your shoulder will make a popping sound and have a minor dislocation. You might then say something like, “dang, my shoulder feels weird. I wonder if I dislocated it.” And that was me. With anterior and posterior tears to my labrum, I skied the following day with one pole; I probably should have put it in a sling.

How I Got to Surgery

The decision or path to surgery was not direct. For the first couple weeks after the injury, I had a lot of pain with overhead and behind-the-back motion. And at first, I was hoping my shoulder would just heal itself, like Wolverine. But after minimal improvements in those first weeks, I scheduled an appointment with my general doctor. He said to take it easy and come back in 2 weeks if there were no improvements.

I came back, then I got an Xray. Then I did PT. Then it still hurt. Then I went back to my Dr. Then I got referred to a specialist. Then the specialist said I should get an arthrogram MRI. Then I got the MRI. Then I went back to the specialist and he told me that my labrum was torn. Then I was sad.

By the time I decided I would get the surgery, it was June; 4 months has passed since I first injured myself. I had good range of motion again, but still couldn’t bench press or do anything overhead without pain. So I decided to go for it.

Pre-Operation

I showed up at the hospital 2 hours before surgery. The asked me to fast — no food or drink after 12 am the night before. Wondering why you fast? It’s because they don’t want you to throw up food and react poorly to the anesthesia. You don’t want complications when you’re knocked out, apparently.

Before they put me to bed, I noticed there were at least seven people in the operating room with me. The nerve block had already been administered by then, in addition to some form of valium. One of the last things I remember was the burning sting of the anesthesia coursing through my veins. And then I lost consciousness.

Post-Operation — At the Hospital (sucks)

Two hours later, I’m awake in the post-op room. People ask me how I am. I’m fine, except incredibly thirsty. I can also see that I am now in a sling. My vitals machine kept going off because of my shallow breathing. I said it was bullshit because I was sitting there intentionally taking deep breaths the whole time, just trying to get the machine to stop. (Of course I know better than the machine when I’m still wrecked from anesthesia.)

Once deemed ready to move to the next stage, they send me to the nurse room. In short: all of the nurses sucked, but they were nice. I was able to retrieve my clothes, and needed to put my shirt back on. A couple nurses tried to help me get my shirt back on, but in the process, my arm fell out of the sling and was hanging in the middle of space. So here I am standing in the middle of the nurse’s room with my shirt off and my arm dead between my arms. Fantastic.

When the Nerve Block Wears Off (Day 1)

I got home and started eating cookies, because I could. Around 9 p.m., the nerve block was wearing off, and I started to take my prescribed oxycodone. Around 1:30 a.m. I laid down in my bed.

And then I started to cry. The pain was unbelievable and continued to worsen. I had already taken more than the prescribed dosage of my painkillers, and based on the recommendations, should not have taken another pill for an hour or two. Around 2 a.m. I couldn’t take it any more. This was the kind of pain that will make you feel helpless. And once you start to feel helpless, you may begin to panic. I just wanted it all to end. I was damn near ready to go to the hospital for morphine or another nerve block, or jump out my goddamned window (I preferred the first two ideas).

I called my dad who was 3,000 miles away since there was a good chance he’d still be up. While being distracted by my father and pacing around my apartment, his girlfriend called my doctor and asked questions about my pain medication, and before I knew it, my doctor was calling me at 2:30 in the morning. (I could not believe it.)

Collectively, we decided that I could take another pill. I did and then slept in our la-z-boy chair that first night. Laying down was, in a word: impossible. In two words: damned terrible.

When You Need to Travel (Day 2)

I slept for about 5 hours before waking up in pain, and I immediately popped another pill. I needed to solve this pain problem. Around 10 a.m., I called my doctor and he just told me to come in as soon as possible. I left my apartment and could barely walk. I slowly struggled my way through the streets of Manhattan for a block or two before hailing a cab. Little did I know that this was about to be the most painful cab ride of my life.

All told, me and the cabbie rode 70 blocks together. Except I was the only one who cried the whole way. You don’t realize how bad NYC’s street conditions are until you experience something like this. I now have a lot of respect for people who drive and have back problems.

I pulled myself together and made it to the doctor’s office. He had me move my arm around a little bit, and again, immediate tears.

For the record, I don’t just cry for Argentina every day; it really just hurts if your painkillers aren’t doing the job.

“Everything looks fine,” he said. And then he prescribed me a stronger dosage of painkillers. This new dosage did the job.

Watching Time Melt (Days 3-30)

The more pills you pop, the faster the seconds will slip away from you. That’s a good thing if you have undergone shoulder surgery, especially on your dominant side. My first check-in came one week later, when my stitches were removed. That was also the first day I got to take a shower, and I was elated to do so.

With all your spare time, what can you do? Well, I wanted to exercise, but pretty much everything was out. I was only allowed to walk. In the third week, I started walking the stairs of my apartment’s building. On the fourth week, I began riding a stationary bike. You can probably start riding a stationary bike as soon as there is no risk of having sweat get into an open wound and risk any sort of complications or infection. I played it safe and waited till week four, though.

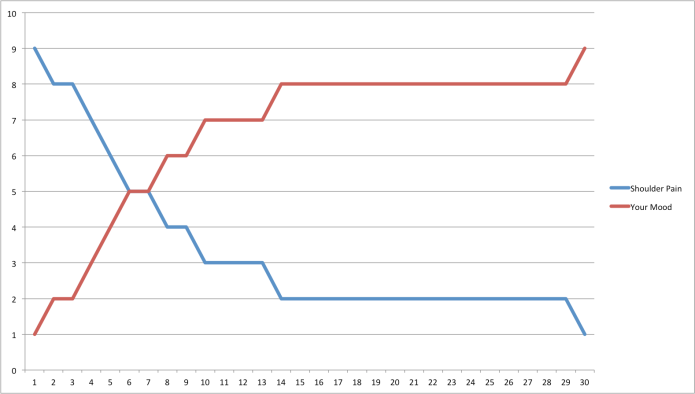

Throughout the time after your surgery, your mood should look about like this (X-axis = time, Y-axis = scale of 1-10. Blue is your shoulder pain. Red is your mood.):

As you can see, you are basically going to act like a moody, drugged teenager on day one.

During this time period, you should also remember to ice. I was provided with this shoulder pack that made me feel like a superhero of sorts.

Below are some of your available activities during this first month of gloom:

Around the thirtieth day, or so, I tried out my ping pong skills. I probably shouldn’t have done this, but I could not resist. Consequently, my right shoulder was pretty sore the next day from being jostled around.

Things You Will Learn That You Took For Granted

- Having two usable hands.

- If you had surgery on your dominant side, your dominant hand.

- All of the things that you have [insert your age – 4] years of practice doing with your dominant hand. Two examples: 1) brushing your teeth, 2) wiping your ass.

- Showers.

- Putting on deodorant.

- Washing your left arm.

- Tying your shoes.

Tying your friends up.- Tying anything.

- Cooking (This didn’t affect me, I just assume it would affect others. I hate cooking.).

- Insurance — the medical claims submitted for all-things-shoulder-related totaled $29,578!!

- Friends/Family — They are what kept me going in the first few days when it was the worst.

Pro-tips

- Prior to surgery, go through your house and think about all of the things that require two hands to operate; find a substitute for them. (Can opening, bottle opening, cooking in general, laundry, etc.)

- Have your shoulder surgery in a place with a warm climate (avoid hot if you can). This will allow you to only have to wear t-shirts/sandals all the damn time, which makes a huge difference. I cannot imagine trying to “bundle up.”

- Buy a pair of Vans slip ons. (Or old-person velcro shoes.)

- Double-check that you have friends or family before doing the surgery. If you don’t, save up a lot of money so you can pay someone to do everything for you.